The most recent South Park episode declares the era of anti-woke satire over. In that light, you might consider this story an artifact of an age just passed. But in truth, I don’t think it is . . . . At any rate, I hope you enjoy this magical romp through the literary world of cancel culture.

“You know,” he said, “we’re not all small. ‘Twas the English who begat that cliche.”

“And we don’t always wear green.”

“And the jokes about the cereal with marshmallows are stale.”

“And that’s not how you spell shillelagh.”

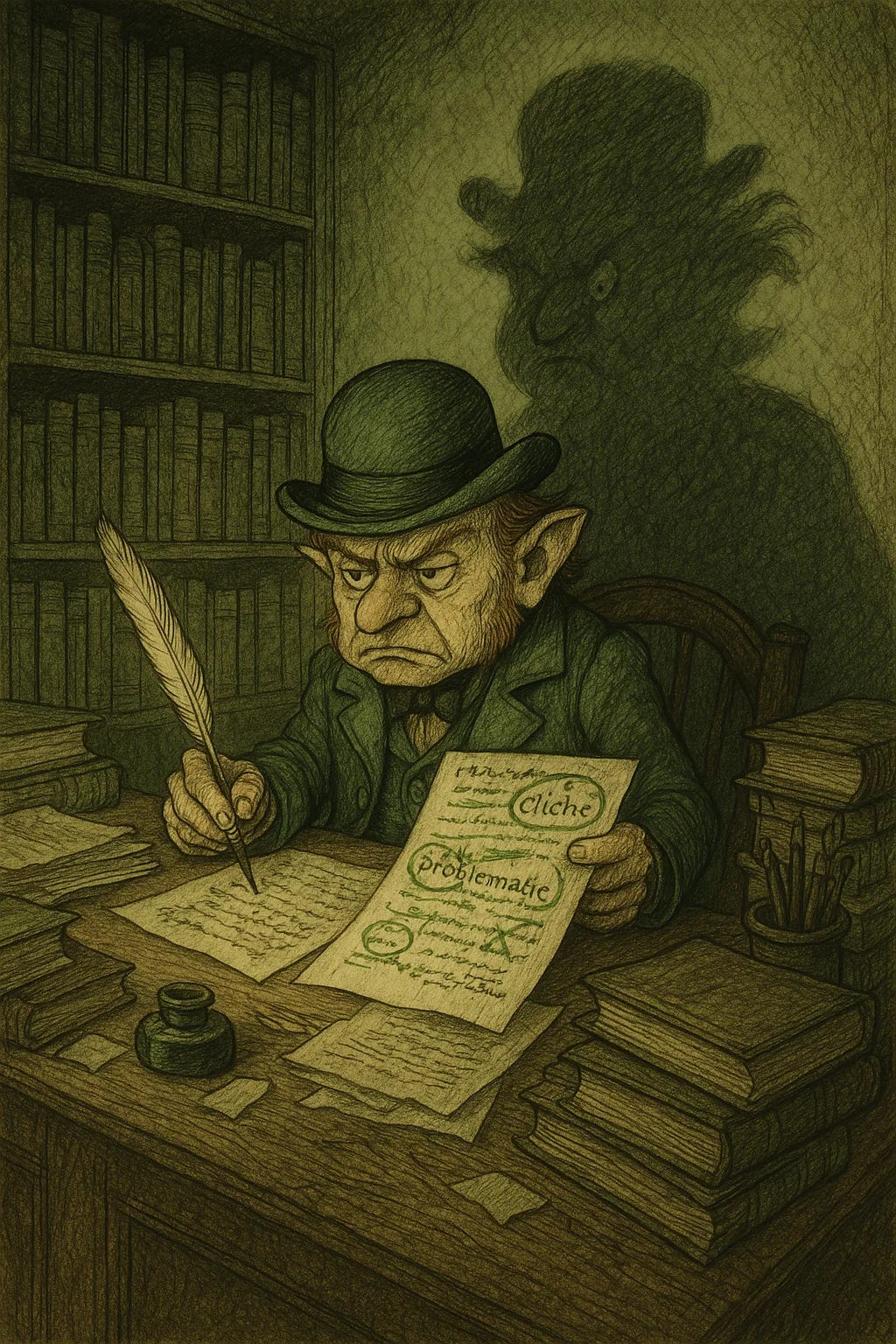

I was starting to wonder about the wisdom of hiring a sensitivity reader for my novel, despite my agent’s insistence. I mean, there he was with his orangey beard sitting in front of a plate of boiled potatoes, dressed in emerald, wearing a bowler hat, tapping my manuscript with a feathered quill, and telling me I was reinforcing stereotypes about leprechauns.

“They’re not stereotypes,” I said. “They’re tropes.”

“They’re slanders,” he said. “Look here, you’ve got your leprechaun hoarding a pot of gold. How would it look if, say, you put a Jew in the story murderously jealous of his shekels?”

“It’s not the same,” I said. “The leprechaun wouldn’t be recognizable as a leprechaun without the gold.”

“Maybe we don’t need to be ‘recognizing’ leprechauns. Maybe that’s just another word for caging us in the prison house of language.”

I could see his point. But I could also see in the corner of his room something that looked like a little black cauldron filled past the brim with shiny yellow metal.

“Look, if I don’t make him from Ireland, if he doesn’t have a pot of gold and a wooden cudgel, I may as well just make him a human.”

“Exactly,” he said, pounding his little fist. “Treat leprechauns like humans. Write about us like we’re human.”

“But you’re not human.”

It was not yet noon, but suddenly the cottage darkened, and he gave me a look so hard I thought he was going to reach for that knobbed stick next to his desk.

“Well, I’m sorry. I mean, you’re a person. But I thought leprechauns were like, I don’t know, a different species.”

“And how do you mean that?”

“Well, I guess, like, can leprechauns and humans--I mean, people who are not leprechauns--make babies together?”

“Are you insinuating something about the size of my organ?”

That reminded me of a joke about a leprechaun with a tremendous schlong standing at a urinal that I had almost, but thankfully did not, include in the novel.

“No, no, just, I don’t know, your DNA, I guess. Is it compatible? Could you impregnate a woman? Could I get a female leprechaun pregnant?”

I didn’t know if there were female leprechauns, but I thought it better not to ask.

“Oh, and are there no human males, males of your species, who can’t impregnate a woman? Perhaps you’re saying that a man with a low sperm count is not human?”

“No. . . .”

“And a female human who’s infertile or who’s had a hysterectomy, is she still a human?”

“Yes, of course.”

“And what about children, are children human before they enter puberty and can make babies?”

“Yes, okay, I see what you’re saying, but you’re not, like, I don’t know, descended from homo sapiens.”

I recalled something I had seen years ago in the Smithsonian about humans having canine teeth that distinguished them from other primates. But the leprechaun hadn’t cracked a smile since I arrived, and I wasn’t about to ask him to let me inspect his mouth.

“And what are homo sapiens? Isn’t that just another way of saying humans? Your argument is tautological and exclusionary.”

“Well, primates then, we evolved from primates. Did leprechauns evolve? I always thought you sort of. . . .”

“What,” he said, and suddenly his speech slowed down and took on a menacing tone, “emerged like dwarves from the earth?”

The shade of his eyes seemed to deepen from shamrock to hunter.

“No. I mean, I don’t know. Yeats said you were a species of fairy.”

“Yeats? Yeats?! Do you mean the Sandymount fascist who went about appropriating indigenous Celtic stories for his transcendentalist doggerel?”

“I thought Yeats was an Irish patriot.”

“Irish, and what do you know of the Irish, much less leprechauns?”

“I took a course,” I said, “in college.

“Begosh and begorrah!” he cried and stamped his little feet. I couldn’t tell if the exclamation was a form of sarcasm or genuine, but it was high-pitched, with a rolling of r’s, the likes of which I’d never heard.

“What did I say?”

“What did he say?” he asked, turning around, his arms in the air, addressing the empty room like an orator. “What did he say?”

I was trying to think of a way to apologize when he reached one hand behind his back, and I glanced at his desk and saw the shillelagh wasn’t there anymore. And then it was, in his hands, and he was winding up like Babe Ruth and, with lightning quickness, smashing the stick against my kneecap, the sound of bone breaking like the crack of a bat hitting a ball.

I bent over, swearing, clutching my leg when he swung again, connecting with my other knee and toppling me to the ground like a lumberjack felling an oak. The pain was so great I couldn’t even plead for my life.

“So,” he said, drawing out his words, “we’re not human? We’re weeee little fairies.”

And then he smiled, and I saw indeed, he did not have canines but something more like a mouth full of molars, designed, it seemed, for grinding bones.

“But do you not know it’s dangerous to be getting too close to the wee folk?”

And the cudgel came up again, but this time he was holding it more like a sledgehammer, eyeing my head like the puck of the high striker at the carnival, ready to ring the bell.

But quick as he was, he didn’t see the feather quill flying up from his desk until it sank deep into his eye, and then I guess he still didn’t exactly see it.

“Oi, you’ve blinded me, you sneaky witch bastard!” he cried, dropping his shillelagh, and cupping his hand against his feathered eye.

Raising myself off the floor with my left hand, I picked up the imp’s stick with my right and gave him a bit of his own back at his kneecap, and he cried out, falling next to me. And there we were rolling on the floor, he half-blinded and half-cobbled, me with two broken kneecaps. He tried applying that mouthful of molars to my hand, but I still had the shillelagh and pressed it into his mouth like a bit as I rolled on top of him. He flailed at me with his tiny little hands as I dislocated his jaw and whispered a spell that caused the feather quill in his eye to spin like the bit of a Black and Decker.

“Quit struggling,” I said, “or I’ll drill it right into your brain.”

He went limp, and I stopped the quill’s spinning, removed it, and flung it across the room. Thick, green liquid bubbled from both his eyes, but I couldn’t tell if it was blood or tears. I cast a binding spell on him, dialed 999 on my phone, and passed out.

I spent six weeks in a Cork County hospital and twelve in rehab, but there was no rehabilitating my reputation. The now one-eyed leprechaun wasted no time. For nearly a week, #areleprachaunshuman? trended, the first post being the imp’s detailed critique of my as-yet-unpublished warlock’s-coming-of-age novel, in which, truth be told, leprechauns played a small part.

When I first saw it, I called my agent to ask what to do, but Angela didn’t answer her phone or respond to my emails. By the end of the week, however, she Tweeted that she regretted her association with me and apologized to the entire magical community. Her agency fired her anyway.

I thought about Tweeting something pointing out that I, as a descendent of Salem martyrs, knew something about stereotypes and persecution. But witches and warlocks had had our day in the sun and were now considered so well-integrated into the human community that we were hardly considered magical.

While I was still in the hospital, I trashed my Scrivener files, and when I got back to America, I threw the MS retrieved from the cottage, with all its green pen marks and annotations, into the fireplace. It went up in a viridescent flash as if it had been cursed, which it no doubt had.

And I thought about the burning of books and the burning of witches and decided the writing business was not for me after all. Better to keep to the shadows as my parents had. But I did take the ashes of the MS and mixed them into a cauldron and blew an ill wind back toward Ireland, where it would cloud the one remaining eye of the wee little creature who had hobbled my literary career.

#paybackisabitch.

Well. That was one hell of a spell you just cast. I sat down to read with a cup of coffee and left with a limp, a lawsuit from the leprechaun union, and a sudden urge to inspect every drawer in my house for cursed quills. You’ve taken the whole tangled mess of cancel culture, literary identity, and mythological diplomacy—and served it up with wit sharper than a fresh-whittled shillelagh.

I nearly spit my drink at “Yeats?! The Sandymount fascist!” and don’t even get me started on the molars. That image is gonna haunt my dreams more than any ghost I’ve conjured.

This story wasn’t just funny—it was smart, spellbound, and sly as a fox in a Sunday hat. And if this marks the twilight of the anti-woke satire age, then you’ve gone and buried it with style. Deep. With bones crossed.

Consider me thoroughly hexed (in the best way).

Yours in ink, ash, and literary mischief,

Chava Hoffman aka Miriam Fay

I hate those little Leprechauns making Lucky Charms unkosher.