There’s a strange little story in the portion of Genesis known as Vayishlach. In this action-packed chapter, Jacob reconciles with his murderous brother Esau, discovers his daughter Dinah has been raped, and flees the region after two of his sons murder a town full of men in revenge. After all that, Jacob’s favorite wife, Rachel, dies giving birth to his twelfth son, Benjamin.

It’s almost as chaotic as an American election season.

And then we get this odd little sentence:

And it came to pass that Reuben went and lay with Bilhah his father’s concubine, and Israel1 heard of it. (Genesis 35:22).

No explanation. The subplot is dropped until Jacob brings it up again during his death bed “blessings,” calling Reuben “unstable as water. . . . Because thou wentest up to thy father’s bed; Then defilest thou it” (XLIV 4).

So what happened? In short, Scripture suggests that Reuben slept with Bilah, one of his father’s four “wives.”2 But Rashi, the great medieval Biblical commentator, calls BS on that.

Reuben, he says, absolutely did not sleep with his father’s wife. Heaven forbid! All twelve sons of Jacob were perfect tzadiks, saints.

What Reuben did was to “switch around his father’s beds.” He was upset because, after Rachel’s death, Jacob moved his bed into Bilah’s tent, not Leah’s—Jacob’s first wife and Reubun’s mother. So Reuben moved his father’s bed from Bilah’s tent to his mother’s.

Why are we told Reuben “lay with” Bilah and “defiled” his father’s bed? Because, says Rashi, the Bible uses metaphor to convey the seriousness of Reuben’s sin. It’s a matter of relativity, you see. For a man of Jacob’s spiritual stature, the seemingly minute matter of rearranging beds was a transgression equivalent to that of a normal man sleeping with a father’s mistress.

I’ve never liked that take. To me, it’s a patent—and regrettable—whitewash of a more probable act. In his commentary to the Soncino Press edition of the Pentateuch, Rabbi J.H. Hersch, “Late Chief Rabbi of the British Empire,” offers this understanding:

It was the practice among Eastern heirs-apparent to take possession of their father’s wives, as an assertion of their right to succession. (131)

According to Hersch, Reuben’s was an act of political rebellion, an attempt to displace his father politically, much like King David’s son, Absolon, who, as part of his rebellion, “went into his father’s concubines in the sight of all Israel” (2 Samuel 16:21-22).3

The problem for Rashi4 is that he can’t bear to think that a Jewish hero should commit such a vile act. We must, at all cost, preserve the image of the Patriarchs and their offspring.

As for me, I’ve never appreciated this impulse. It’s the Biblical equivalent of rewriting the Han Solo seen in Star Wars so that Han doesn’t shoot first because, well, you know, that’s not very sporting of him.

What Rashi and others like him are doing is engaging in Biblical retcon—a retroactive rewriting of a story to align it with either the new realities or new values of a later audience.

You see this sort of thing a lot in popular culture. A relatively innocuous example would be the altering of the Iron Man story so that Tony Stark invents his supersuit during the Gulf War as opposed to the Vietnam War, thus bringing the whole story forward a few decades for a younger audience.

The Han Solo retcon was far more controversial, representing George Lucas’s rethinking of the Han character as a kindler, gentler figure who would never sucker shoot a bounty hunter. Thus, in the newer releases of the original film, the scene that constitutes our first introduction to this character scene is altered so that the bounty hunter shoots first, misses, and is then shot by Han.

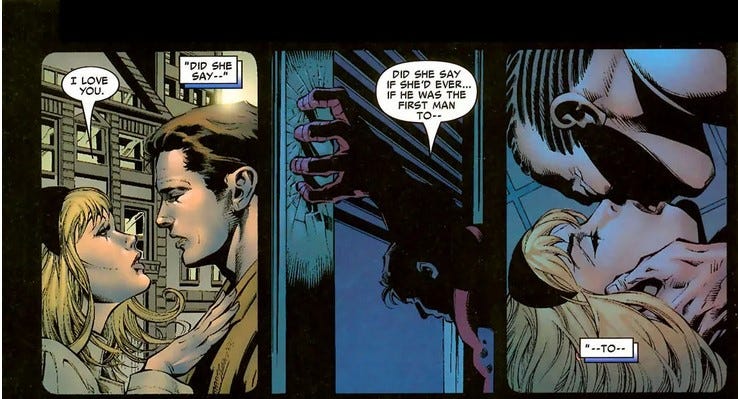

The absolute worst retcon in the universe (from which I drew the cover panel for this post) was the decision by Marvel writers to imagine, decades after she was killed off in the comic book, that Spider-Man’s girlfriend, Gwen Stacy, had been secretly sleeping with Norman Osborn, i.e., the Green Goblin, a man old enough to be her father, and had given birth to two super-powered twins as a result of that relationship. The inverse of rabbinic retcons that seek to rehabilitate the reputations of sacred characters, this retcon spoiled for many readers a sacred figure. In fact, so appalling was this retcon that the retcon has been subsequently been retconned out of existence.

In Judaism, we don’t call these sorts of things retcons but “Midrash”— a tradition of Jewish scriptural interpretation that seeks to fill in gaps and provide alternative readings of Biblical narrative.

What I would consider a harmless example of Midrash would be the famous story of Abraham in his father’s idol shop. Abraham, so the story goes, decided one day to take a hammer to all his father’s idols, all but one. When his father came home and found the idols destroyed, he accused his son of wrecking them, but Abraham said the act was committed by the last remaining idol. “But it’s a lifeless statue,” his father exclaims, to which Abraham answers, “Exactly.”

There’s no idol shop in the Bible, much less this whole hammer tale, but this little retcon works smoothly with everything we know about Avraham, and so, while I don’t take it literally, I find it kind of charming.5

But when Midrash fundamentally interferes with the trajectory of a character, I start to have problems. Take, for example, the aforementioned King David.

Do you recall the story of how he spied the beautiful Bathsheba bathing on a rooftop and was so filled with lust for her that he sent her husband off to die in battle just so he could sleep with her? Leonard Cohen memorializes the scene in his famous song “Hallelujah”:

Your faith was strong but you needed proof

You saw her bathing on the roof

Her beauty and the moonlight overthrew you. . . .

Well, according to the Rishonim, that’s not really what happened.

I first heard the alternative version in a lecture by Rabbi Tatz, a South African rabbi at Yeshiva Ohr Somayach.6 According to Tatz, the standard version of the story is borderline antisemitic. “If you believe that’s what really happened,” he says, “I don’t know how you could be proud to be part of the Jewish nation.”

King David, he argues, was “so incandescent with spiritual power. . . .that if you got a glimpse of him, you would have died.” And yet we are to believe “he did such a crude and coarse averah?”

Quoting the Talmud, Tatz explains that David was not lusting for a married woman. No, what happened was that the King saw through prophetic vision that from his union with Bathsheba would come King Solomon and from Solomon the lineage that would ultimately result in the coming of the Messiah. David’s real sin was not lusting after a woman but impatience for the Redemption.

This is absolutely not a whitewash, Tatz avers. On the contrary, Judaism is unique among other religions in refusing to paint over the flaws of its heroes, and he cites by way of example the inclusion in Scripture of the story of Moses’s punishment by God for bringing forth water from a rock by hitting, instead of speaking to, it.

But this is actually a counter-example. By the Rashi/Rishonim/Tatz standard, God’s punishment of Moses for such a small act of disobedience should be incomprehensible to the average reader. If Scripture wanted to bring home to us regular folk the seriousness of Moshe’s crime, it should have told us instead that he lay with his sister or some such thing.

The idea that David was turned on spiritually by Bathsheba makes no sense logically or narratively. It’s not like the King noticed her davening on the other side of the mechitza at shul and thought, “What a holy woman!”

He saw her stepping naked into a bath. And we’re supposed to believe he was thinking of the Messiah?

I mentioned this to a guy at synagogue the other day, and he said something like, “Think of it this way. King David wrote some 75 psalms of supreme holiness. Can you imagine such a man could lust so coarsely after Bathsheba?”

To which my response was, “Yes, definitely.”

We all know by now that artists are not saints. (And if you don’t, you might want to read my Substack on Alice Munroe or my Quillette article on Roger Waters.) You don’t need to be holy to write holy verse. On the contrary, one might argue holiness works against art.7

“Art requires that you have at least gone through a period of brokenness,” says writer Andrew Klaven8. “You have to have something broken in you to be an artist.”

Really, what seems more likely? That the greatest poet in the Bible was a bit of a cad, a bit of a player, a Byronic figure, or that he was the Hebraic version of Dudley Do-Right?

Children need flawless heroes. Adults don’t.

When they are small, children believe their parents are godlike. When in adolescence they learn otherwise, they may become so angry that they reject them. But when healthy children grow up, they learn not only to forgive their parents for their limitations but also to admire them for what they achieved despite those shortcomings.

In our current climate, we seem stuck in the adolescent phase of rejecting flawed heroes, our cultural parents as it were, which is why not only Thomas Jefferson and George Washington but also Martin Luther King, Gandhi, and Mother Teresa have become problematic. I’ll spare you the links, but Google any of them, and you’ll dig up an impressive amount of dirt and discover why some would like to revoke their heroic status.

Of course, you don’t have to Google King David to get dirt on him, and that’s the wonderful thing about the Bible. Hertz writes:

It is the glory of the Bible that it shows no partiality towards its heroes; the are not superhuman, sinless beings. And when they err—for ‘there is no man on earth who doeth good always and sinneth never’—Scripture does not gloss over their faults. (47)

Scripture might not gloss over faults, but the commentators sure do, from the Rishonim to today’s Torah influencers. But as deferential as I try to be to Torah authorities, this is one part of the program I just can’t get with.

I don’t need to pretend Biblical figures were angels or “incandescent,” miles above me and everyone else in terms of holiness. On the contrary, I prefer to think they weren’t that far out of reach.

It’s not because we’re the descendants of spiritual superheroes that I am proud to be a Jew. I’m proud because we are a people who have always aspired to be better than we are.

Likewise, count me out of any attempts to cancel secular heroes because we’ve dug up dirt on them. As with Scripture, we should note those flaws but keep them in perspective, placing their private sins in the context of their greater public deeds.

i.e. Jacob.

Two were legally married to him, Rachel and Leah, the other two were given to him by his wives when they themselves were unable to bear him children.

Of course, you could see this explanation as a milder form of whitewashing since it suggests Reuben’s motives were political rather than, say, hormonal. That he wanted to seize power is more dignified than that he had carnal desire for Bilah. (And yes, “carnal desire” is a whitewashing of the phrase I first thought to use.)

To be fair, Rashi is drawing on previous commentators and writers of Midrash. I use his name this way for convenience, but he didn’t develop these ideas independently.

There’s a saying to the effect that anyone who believes midrash stories is a child; anyone who denies them is an apikores, i.e. a heretic.

I’m going to be hard on Rabbi Tatz here, but I owe him immense gratitude for all that I learned from him through the eighty hours or so of his audio recordings that I listened to during my first year of studying Judaism. He’s a smart, deep thinker, and his lectures can be addicting.

In my experience, some of the worst fiction ever written has come from Orthodox writers determined to produce holy and wholesome stories.

Toward the end of episode of 1192 of his podcast.

David wrote those psalms BECAUSE he was lusting after Bathsheba and every other hot piece of desert ass that wandered into his view. Sublimated sexual passion is the most classic of all Muses.

Passion for one's God and one's People is supposed to come from a flaccid, indifferent male? Dream on. Passion is passion. David was a roaring old goat which is why he was King.

Interesting post. I’m not Jewish but grow up Catholic. A few years ago I read Genesis using Alter’s translation and Prager’s, Sacks’, and Sarna’s interpretations. It seems to me that the best way for me to read Genesis, the way to make it come alive, was to see the characters as individuals with human characteristics, not as supernatural creatures with superhuman characteristics, living amongst a God that cared about them. While I understand that Hebrew is pliable and open to different translations and interpretations, and that the works and interpretations of other people and Rabbi is important, too many times they are in the service of an established religious tradition and Orthodoxy. There are too many things in the Bible that are contradictory and seem to be in conflict with orthodoxy (for example I find the bit where nephilim and sons of gods walkes the earth strange for a monotheistic religion).

Your comment about King David is accurate— he was a man that was overtaken by eros, who wrote beautiful poetry, a subject that Plato would not have trouble understanding.

But in the end, it seems like Genesis is the story of “human stuff” living in divine presence, people who are not perfect but like us. Otherwise, whitewashing is wishful thinking.

I would rather take man for who he is, and examine what he aspires too, and how he ticks; the Bible can be how that ticking is a manifestation of the divine, sometimes failing but always hoping.