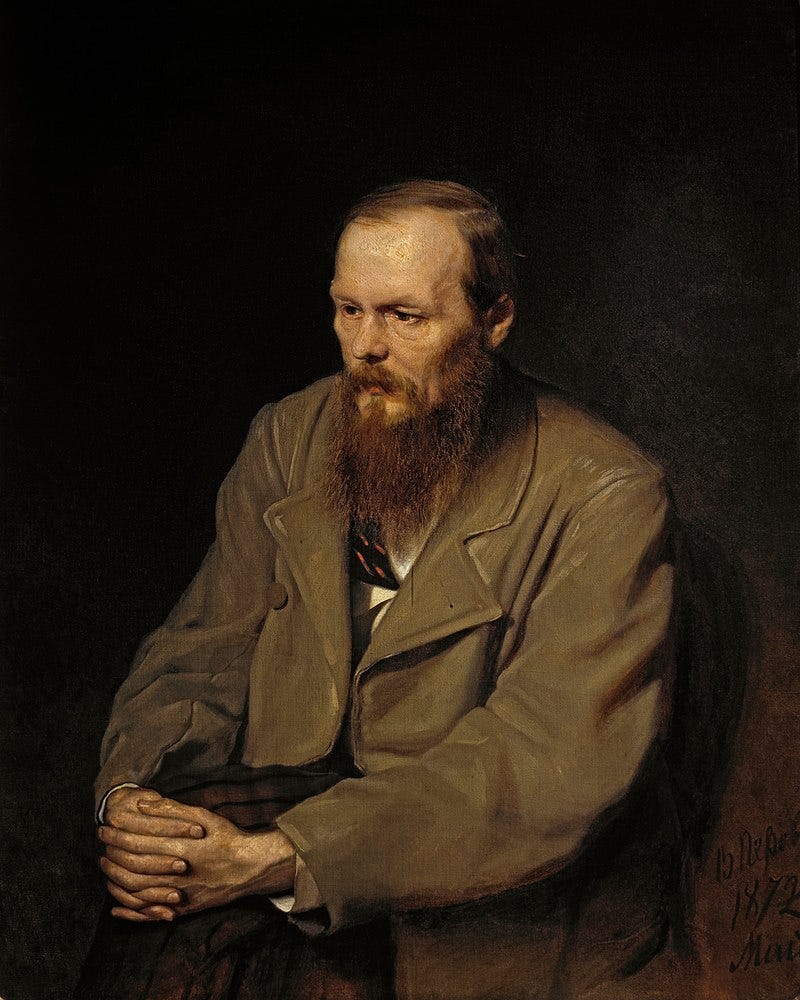

I always feel pretentious when I deploy the name “Dostoevsky”—and I always need spell check to help me do so correctly.

There was a time when I thought of him only as the guy who wrote that repulsive little book, The Underground Man, later as the author of a seemingly overrated and hard-to-follow book, The Brothers Karamazov.1

Then, sometime in my fifties, I found his novels more interesting and entertaining, even if I still broke my teeth over the Russian names and had to look up chapter summaries to make sure I understood what I had just read. Mostly, I listened to them on Audible,2 which may account for some of the comprehension difficulty. You have to focus on Dostoevsky, and even washing the dishes can make that tough. Suffice it to say, I no longer found him pretentious and obscure but strangely uplifting. Reading him made me feel smarter and deeper, so much so I coined a mantra to get myself off the news and social media: “You could be reading Dostoevsky.”

And then, of course, I found out he hated Jews.

I heard about it recently on Substack, and I’d give credit to the writer if I had done more than read the headline and if I could locate the article.3 I learned more when, in preparation for a piece on Roger Waters, I perused an article on Mosaic, “Why Dostoevsky Loved Humanity and Hated the Jews.”

There, writer Gary Saul Morson lays out a basic problem with the great Russian author:

Dostoevsky’s devotion to compassion could not have been more fundamental to his thought and art. . . . (and he) was deeply compassionate in his personal life. . . .[But] How bad an anti-Semite could he have been? Very bad indeed.

I’m not going to do a deep dive into Dostoevsky’s antisemitism. If you’re interested, I suggest you read Morson’s article and its two responses in Mosaic. But, in a nutshell, Dostoevsky saw Judaism as a pernicious ideology that fomented injustice and suffering—in opposition to a Christianity rooted in mercy, empathy, and self-sacrifice. The writer looked forward to and advocated an apocalyptic overthrow of this Jewish mindset.

Dostoevsky, of course, like our friend Roger Waters, vociferously denied being anti-semitic: “When and how did I declare my hatred for the Jews as a people? Since there was never any such hatred in my heart . . . I, from the very outset, reject this accusation once and for all.”4

To which most of us will respond, yeah, sure.

But the purpose of this post is not to indict Dostoyevsky as a Jew hater. It’s certainly not to cancel him. I have written more than once, most recently about Alice Munroe, about my steadfast opposition to dropping art because of the artist’s failings.

I’m also not interested in explaining or exploring the roots of Dostoevsky’s Jew hatred, as the Mosaic writers attempt.

What I want to explore is how a writer can be so on in his novels and so off in his other publications. And, even more importantly, how might I and other writers avoid Dostoevsky’s missteps and use writing to express our better, not worse, selves?

The Artist as the Better Self

A central point of my article about Roger Waters’s repellent statements about October 7 in Quillette5 was that “the work is superior to the person who produced it; the writer writing is better than the writer him or herself. . . . Dostoyevsky, the novelist and the narrator of stories, was a better person than the man who shared his name.”

I’m not alone in this belief. In his Mosaic response to the Morson article, Adam Kirsch writes,

It may seem paradoxical for the man to be smaller, spiritually and intellectually, than the writer, but in fact that is usually the case with great artists.6 What they do and even what they think is not much different from the people who surround them. For a Russian patriot and Orthodox believer like Dostoevsky, it would have been almost impossible not to be anti-Semitic, just as it would have been almost impossible for a writer from the American south like William Faulkner to be free from the prejudices of his milieu.

The greatness of such artists lies, rather, in their ability to evade their own limitations when creating art.

Such arguments don’t “excuse” Dostoevsky from antisemitism any more than they “subsidize” Alice Munroe’s abysmal parenting; it simply describes a situation that is, in fact, true for almost everyone, not just artists.

The plumber is a better man when he is plumbing. The physician is a better woman when she is doctoring. Almost all of us have a different work than home persona, and almost always, it is a better version of ourselves. People unable to make this separation often don’t fare well in the work world.

But this begs the question: Wasn’t the Dostoyevsky who wrote antisemitic tirades also a writer? Wasn’t he also an artist?

Yes to the former, a qualified no to the latter.

Dostoyesky’s most virulent antisemitic remarks and ideas are found in his journalism, not his novels, in which Jews and Judaism occur rarely.7 The worst stuff, according to Morson, is found in a monthly column he wrote: A Writer’s Diary: A Monthly Publication. I have not read any of these, so I am relying on Morson’s summaries and quotes for my understanding of the diary. But it seems to me that what we have here is journalism, not art, maybe even a kind of precursor to social media,

While drafting The Writer’s Diary, I suspect that Dostoevsky did not engage that higher self of the novelist, the one with greater empathy, a greater willingness to set aside ego, the one driven by a desire to create instead of tear down. He put aside that higher self so that he could indulge pet theories, repeat slanders, prevaricate, take the narrowest view of his subject, and the result is we see a man who perhaps is not only not better than his ordinary self but probably not as good.8

This is an important lesson for artists who, unlike plumbers, can more easily talk themselves into believing they have special powers of observation in fields, not their own.9

“Dostoyevsky believe[d] [he could see] deeper into historical forces than anyone else,” Morson writes. He explains that it was common in Russia for people to believe that great writers could do that, but actually, the belief in the special powers of writers was pervasive across Europe and America throughout the nineteenth century and beyond.

You can trace this attitude as far back as William Wordsworth’s A Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, in which he writes that a Poet10 is a man unlike other men:

a man. . . . endowed with more lively sensibility, more enthusiasm and tenderness, who has a greater knowledge of human nature, and a more comprehensive soul, than are supposed to be common among mankind; a man pleased with his own passions and volitions, and who rejoices more thanother men in the spirit of life that is in him. . . .

By Poet, I take Wordsworth to mean writer/artist, and his point is that writers see more deeply, feel more deeply, express themselves more profoundly, than others. Elitism? Sure. But is it true? I think so—in a qualified way.

When the Writer is engaged in true or “proper” art (more on that later) he or she does see more deeply, feel more deeply than when not thus engaged. The problem is writers don’t always understand that this superpower doesn’t extend to all areas of writing. They may have the same social security number, but the person shit-posting on X is not the same person writing poetry for The Kenyon Review.11

Even prophets, I’m sure, were not prophets all the time. I can imagine Moses or Isaiah or Jeremiah saying stuff at table we wouldn’t want recorded in scripture.12

And for an artist to access their prophetic voice, I would argue, they must engage in art, not journalism, much less social media. This is not to say they shouldn’t engage in punditry—or post on X—only that when they do so, they should not fool themselves into believing that they are drawing on their best self or their prophetic powers.

But it’s not always so simple to know when you’re writing from your best self.

Static Vs. Kinetic Art

As a fiction writer and an essayist, I consider myself an artist, but I don’t consider everything I write to be art, and sometimes it’s a challenge to know the difference.

I think I know when I’m in that better self zone. It feels calmer, more serene than when I’m writing out of it. I have no desire to “throw shade” or “own” my opponent. And yet, how can I be sure?

I can’t, but I think I may have some guidelines, and for those, I turn to James Joyce, an author who, I’d argue, always remained faithful to the muse.

In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Joyce’s protagonist, Stephen Dedalus, makes the following observation:

The feelings excited by improper art are kinetic, desire or loathing. Desire urges us to posses, to go to something; loathing urges us to abandon, to go from something. These are kinetic emotions. The arts which excite them, pornographical or didactic, are therefore improper arts. The esthetic emotion (I use the general term) is therefore static. The mind is arrested and raised above desire and loathing.

Kinetic art, Stephen suggests, is an “improper art” in that it seeks to provoke a desire to do or possess, whether that’s buying a Coke (advertising), losing mastery of your domain (pornography), or changing your views (punditry). “Proper art” is static; we are raised above simple desires and resentments. We are content to be in the work and don’t need to do anything.

These, of course, are not firm distinctions. Was Dickens being kinetic and improper in Oliver Twist when he ironically declares, “What a novel illustration of the tender laws of England! They let the paupers go to sleep!” Was he not trying to inspire social change? Is that not a kinetic aim? Does that make the novel improper art?

Are George Orwell’s novels 1984 and Animal Farm works of kinetic art and, therefore, “improper?”

For my part, I think it’s a fair criticism of Dickens to say he’s sometimes didactic, and I think it’s questionable whether 1984 is a very good novel despite my absolute certainty that it’s top-notch totalitarianism trolling. Animal Farm, because it functions so well on both levels, is a horse of a different color.

When my son read Animal Farm at age 12, he had no idea it had any political content, only that it was a terrific story. I had the same experience when I was shown the movie in fourth grade. Only upon instruction was I or he able to see that it was an allegory of the Soviet communist revolution. In that sense, Animal Farm is a unique and unprecedented blend of static and kinetic.

I know that some people think art must be political. I’ve heard them say so. Orwell said so. But I’m not one of those people. I am on Joyce’s side. Daedalus says:

The artist, like the god of the creation, remains within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible, refined out of existence, indifferent, paring his fingernails.

What he means here is that the artist doesn’t make editorial remarks about his characters, doesn’t set things up to punish the wicked and reward the good, but I’d extend this to the idea that the true artist, like God, rarely and only in great need, interferes directly in human affairs.

When an artist becomes a pundit, when a writer moves from the static to the kinetic realm, he or she steps outside and even transgresses their vocation, which is why it can feel so hurtful to their audience and why it should not be done lightly.

But sometimes, it is necessary.

Transgressing the Vocation

Consider the following examples.

Matthew Arnold lately has yet to make an appearance into my Substack, but he is one of my favorite poets and a literary hero, so much so that years ago I started on Facebook The Matthew Arnold Fan Club.13

In his day, Arnold was ranked as one of the Big Three of Victorian verse: Tennyson, Browning, and Arnold. But somewhere around mid-career, he stopped writing poetry and turned to criticism because, he decided, the world needed that more than his verse.

Like us, he lived in a time of tumult and revolution, literally, as in the year 1848 when revolutions sprang up all over continental Europe and when the English were pretty sure they were headed for their island. Events like the Hyde Park Riots particularly alarmed Arnold. The result was that he abandoned the muse of verse and picked up the pen of punditry—and went on to write some of the most important criticism of the Nineteenth Century, including the classic Culture and Anarchy, which every literary person ought to know.14

Arnold abandoned his vocation as a poet because he saw the world in trouble and felt a responsibility to intervene. He was able, moreover, to articulate a unique vision of the problem and the solution in ways no one else could. In some ways, we owe much of what we consider the study of literature to his advocacy of turning to art for meaning.

In our own time, in a much more limited, focused, and fiercer way, J.K. Rowland exemplifies a writer who saw a need and stepped outside her artistic sphere to tackle it. In her case, unlike Arnold’s, she has no unique vision to share. Her view on transgender ideology is commonplace. The difference is that no one else of her cultural stature was willing or able to speak out publically on the excesses of this movement for fear of excommunication from polite society, loss of income, and even the threats of violence. With the vast treasury of good will she amassed through the success of Harry Potter, she was in a unique position to take the hits that would inevitably come when she questioned what was quickly becoming accepted dogma both in culture and law.

Some have accused her of squandering her legacy. But I would argue she leveraged it for a higher cause.

What sets Arnold and Rowling apart from many other artists who leave static for kinetic endeavors is that they have something irreplaceable to offer. In Arnold’s case, it was his penetrating insights and eloquent argument; in Rowling’s case, it was the sheer force of her personality and reputation combined with her immense reach.

In Dostoeyevsky’s case, however, he neither contributed anything unique nor performed a service only he could perform. There may have been some innovative elements in his particular brand of antisemitism, but it didn’t reflect his true vision, and there were plenty of other Jew-haters around to do the job.

In our day, it’s common for writers to take time out from our vocation—and withdraw from the bank of good will—to engage in punditry, but when we do, I believe we should first try and meet the test exemplified by Arnold and Rowling. We should be able to answer yes to one or both of the following questions: 15

Do I have something important to say that no one else is saying?

Am I in a position to say something important that other people believe but cannot say (or get heard)?

Self Reflection

These are the two questions I ask myself before writing articles or substack posts that feel kinetic.

For example, several years ago, there was a lot of hoo-ha about the “banning” of the graphic novel Maus in a small Tennessee school district. People were accusing the district of antisemitism and the suppression of Holocaust history. But I had not only read Maus, I had taught it at the college level, and the entire tenor of the conversation seemed off-kilter to me. As a second-generation Holocaust survivor, a professor, and a comic book aficionado, I figured I had a special vantage point on the issue. I searched the Internet for people saying what I was thinking about the controversy and found no one doing so, so I wrote about it myself.

Then last week, after the assassination attempt against the former president, I posted my support for Trump because I felt like there were few people in my position—fiction writer, full professor of English—who could demonstrate that an educated, creative, thoughtful individual could support him and that I had a responsibility to stop hiding, to set an example.

Both decisions upset people. Jewish writers I knew all but called me a nazi for writing the Maus article, and a few Substack readers saw my post as a kind of betrayal—or an unpleasant unmasking.

I still stand by both pieces, but I’ll admit there are some kinetic elements in each that did not fit my criteria.

In the Maus article, I included a paragraph that maybe didn’t need to be there taking to task “the left” for exploiting the controversy. In the Substack post, I went beyond my confession of support for Trump to attack progressives for demonizing him. I didn’t say anything untrue, but it was certainly not a unique perspective; X, if not Substack, was aflame with posts making exactly the same point.

In both cases, I was under pressure to be timely, which is another aspect of “improper art,” one might argue. It’s one thing to meet an editorial deadline, but the need or desire to get a work out while the news cycle is hot feels to me like a counter-wind to proper art.16

In the end, I sometimes find it hard to know whether I’m engaging in artistry or punditry or some hybrid of the two. Even in this post, I’ve asked myself several times am I reflecting creatively or arguing rhetorically? Am I stepping outside my vocation for a good reason or to vent spleen? Am I using whatever limited platform I have to make something beautiful, or am I misusing it for a lesser purpose?

As with so many things, sometimes, I’m sure of myself. Sometimes, I’m perplexed.

Which I only read because a friend told me he reread “The Grand Inquisitor” chapter at least once a year because it was that important.

How do I monetize this product placement?

Hint to Substack engineers. Can you please give us a history button and some better search tools?

Quote from the Morson article.

Which, unfortunately, is now behind a paywall.

Though the wording here is close to mine, I didn’t read the Kirsch article before writing the Waters one. I had only skimmed the Morson one. I guess we were just on the same page.

However, when they occur, the Jewish characters always seem to be characters in the vein of Dicken’s Fagin, but mostly as comic asides.

Because, at least as portrayed by Morson, in person, Dostoevsky was a pretty good guy, unlike, say, Waters, who nearly everyone agrees is, in person, kind of a jerk.

Actors and celebrities do this too but with far less warrant, given the nature of their profession.

And yes, capitalizing the word was his way of reinforcing the divine nature of the vocation.

In truth, I’ve never read a single issue of The Kenyon Review and am just name-dropping here, and for all I know, they publish a lot of poetry that might contradict my point.

The Chosen kind of illustrates this with JC, though he never really says anything you could hold against him. He just kind of goofs around sometimes.

I don’t believe its membership has ever exceeded 4, including bots. Feel free to join. We have meetings every Sunday, but no one ever shows up.

Yes, I said “ought.” I’m not just an artist. I’m also a school teacher.

Stephen King, I think, is a good example of a writer whose work I admire but who, it seems to me, posts nothing in the way of social commentary that hasn’t already been said and couldn’t be said just as well by someone else.

Though you could also argue that part of art is timing.

For Waters to think that he is an existential threat to the Israeli government (as he helpfully explains in the video you linked) is laughable beyond belief. Waters is less than an annoying mosquito. An irrelevant has-been (or if we believe David Gilmore) a never-was

It's sad that Dostoyevsky, one of the greatest writers who ever lived, was also an asshole Jew hater. But it is what it is. He was certainly the rule, not the exception, in 19th century Russia

I found Notes from Underground a very insightful book into the mind of the mediocre, isolated man.

Unfortunately, there isn't enough justice in this world to guarantee that the base and antisemitic people will be failures in their work.

Werner Heisenberg was one of the founders of quantum mechanics and his operator-based formulation has far reaching impact even today in mathematics. He also led the Nazi Atomic Bomb project.