The following is the “director’s cut” of my article published this week in Quillette. I’m pleased, as always, to be published in the leading heterodox journal on the web. They needed a more compact, less colloquial version, and if that fits your needs, check it out at AI and the Death of Literary Criticism.

Maybe it’s just the end-of-the-semester blues,1 but I don’t think so.

I don’t see how college English Departments can survive the coming technological tsunami—and maybe they shouldn’t. And I say this as a full professor of English, who loves teaching and believes in the power of the written word.

The world is replete with articles about declining English major enrollment. See here and here, and here. And, yes, I can attest that enrollment in the department in which I teach has declined some 50% since I was hired in 2007.2 Literature tracks are doing particularly poorly compared to Creative Writing, but we’re all in decline. To get students into our classrooms, we must entice them with sexy posters and patronize them with courses like “Reading the Vampire.”3

Some will say it’s because of changing demographics, because of economics, because departments have become leftist propaganda outlets. I’m apt myself to support the latter charge, but it’s neither economics nor politics nor even evil Republicans out for revenge that are going to deal the death blow to English Departments.

It’s AI.

When ChatGPT can analyze Hamlet as well as any grad student, we might reasonably ask, “What is the point of writing papers on Hamlet?”

Literary analysis, after all, is not like building houses or feeding people or practicing medicine. It lacks even the self-evident justifications of some of its sister disciplines in the humanities, such as history or philosophy. The study of literature serves no practical need whatsoever—and besides, when machines can build houses as easily as people, we won’t need people to build houses either.

But let’s back up. Why do we have English Departments in the first place? Why do we teach English?4 Whatever reasons we had to do so in the past are all but obsolete.

Key the Flashback

When the whole thing began,5 the idea was, in the words of the great 19th-century Brit crit Mathew Arnold, “to know the best that is known and thought in the world, and by in its turn making this known, to create a current of true and fresh ideas.”

Back then, we had a pretty good idea of what was “the best that is known and thought”—Homer, Sophocles, Virgil, The Bible... and in English, Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, eventually Blake, Hardy, Joyce, Virginia Woolf. There were debates here and there about who or what was the best, the greatest. Was Blake a genius or a nut? Was Dickens serious literature or sentimental claptrap for the masses?

The so-called “canon” of great literature was open for debate and evolved. But greatness itself was not. The reason for reading was not. To paraphrase the so-called New Critics who ushered in the rise of serious literary criticism, we read to make ourselves better people—deeper thinkers with a great understanding of humanity, people who were more empathic, people capable of critical thinking.

It was, in truth, a substitute for religion. We wanted people to be good, but we didn’t believe in God anymore. We believed in Shakespeare, we believed in Milton, and eventually we even believed in Toni Morrison. Until we didn’t.

It’s always been a problem, this idea that literature makes you a better person. Besides the obvious counterfactuals—“You know they found copies of Goethe in the desk drawers of Nazi prison guards when they liberated the camps,” my father once told me—there was always the problem of pushing our religion on other people.

Our religion, my religion, was Literature.6

Like any people of true faith, we deeply believed in it, thought it was essential, thought everyone must be saved through it. The remarkable thing was that we somehow convinced college presidents of the idea, but then, again, many of them, like University of Chicago president, Robert Hutchins, creator of the “Common Core” and advocate of “Great Books,” were members of the same religion.

So for some fifty years, we evangelized and pushed our religion onto college students, some of whom, such as myself, were already in love with reading and so happy to worship at the Temple of Literature. Many were not, but for a century or so, we rammed down their throats Shakespeare, Melville, and, yes, eventually Morrison. Why? To Make them Better People.

Instructive Digression

When I was in Hungary in the 1980s, before the fall of communism, I discussed education with some of my cousins. They told me that, under Soviet Domination, from elementary school, they learned Russian.

“Oh,” I said, “then you must all be fluent.”

“We don’t know a word of Russian,” they told me.

Lesson: you can force a kid to “learn Russian” because it’s “good for him”—but you can’t.

You can force a kid to read Hamlet. But you can’t. Because even if you can, he will forget it two minutes after you test him on it.7

You have to believe in Literature to benefit from studying it, and let’s be honest, most students never did. Maybe that was in part because of bad teaching. Not everyone can be Robin Williams in Dead Poets Society, standing on top of his desk and seducing his students into a love of Walt Whitman—and in truth, even he could only reach a minority of students.

Some students with the right temperament and intellectual predilections are drawn to the Temple of Literature, but most are not. For most, it is like going to Sunday school, like going to Hebrew school, and we all know how that works out. . . .8

Back to History

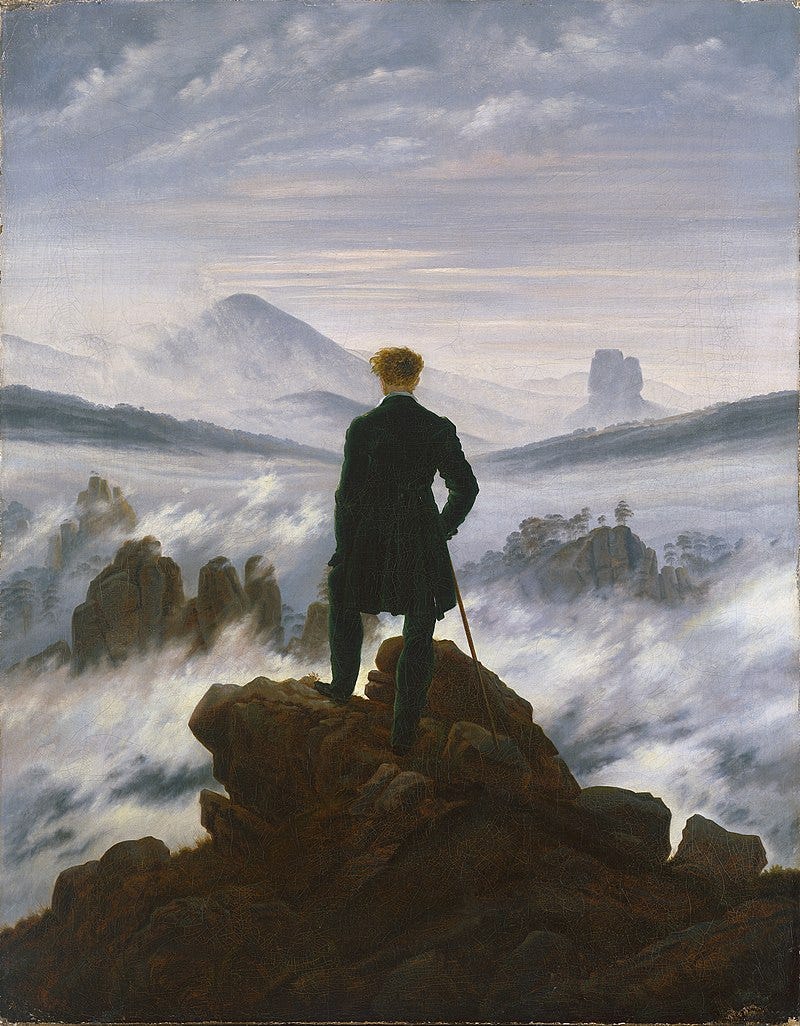

And then the Sixties came, and things were still okay because critics like M.H. Abrams and Northrop Frye spiritualized literature in ways that felt compatible with the hippy culture in ascendance. William Blake and the Romantics came to the fore, even visiting Allen Ginsberg in his dreams.

The Seventies saw the opening of the canon to a wider range of writers, more women, more people of color. And you could still worship literature and feel good about it—even if some feminists and Marxists would tell you that D.H. Lawrence and Hemingway were misogynists.

But the mainstreaming of “deconstruction,” “post-modernism,” “post-structuralism,” and that ilk in the 1980s spelled the beginning of the end, as it tore down completely the spiritual/religious underpinnings of English as a discipline.

First of all, there was no rescuing the canon through expansion. The whole thing had to go because “the best that is known and thought,” it was alleged, was just code for “what keeps powerful white men in power.”

Second, “literature” was demoted to “text.” There wasn’t anything special about, say, Moby Dick. You could read it the way you read the label on the back of a soup can—or vice versa. You could read the back of a soup can as a text no less interesting than Melville’s novel.

True story from grad school: A friend of mine—now a prestigious professor of American Studies and Gender and Queer Studies—had to read Moby Dick for the first time to pass her oral exams.

“You know what?” she said to me. “It’s actually a really good book.”

She went on to write her dissertation—for a PhD in English Lit—on the rhetoric of wedding dresses or some such thing.

At this point, the religion of Literature became the religion of Text. You didn’t read to learn anything from “great authors.” Authors didn’t even exist anymore. You read to learn skills in analysis and deconstruction.9 And you read to learn how to critique—i.e., attack—the cultural legitimacy of the text and the culture itself.

This is where English departments turned into greenhouses for growing leftists, which is why conservatives are so gleeful about their decline.

But, if we want to be fair, English Departments were always ideological. English professors were Priests of “Culture” until they turned the house on its head and became the anti-priests of culture, evangelists not of art but of dismantling texts to “fight the man.”

Sunday School Teachers Are in Trouble?

In either case, the average kid coming into an English class—unless he or she was a true believer or a convert—was, yet again, subject to a glorified Sunday school/Hebrew school teacher, forced to learn the catechism, to learn their Aleph-Bet.

And like my Hungarian cousins, few became fluent.10 Most didn’t learn either Literature or Text, but rather learned to get by or get over their teachers.

They got over, by plain old cheating, copying answers, getting other kids to write their papers, plagiarizing. Now they get over with AI.

They got by—and some still do—by suffering through the novels and poems, parroting back to teachers what they knew they wanted to hear, and then forgetting everything they “learned” the moment they’d been graded.

Thing is, up to now, we Sunday school teachers still had the power. We could still make the kids do what we wanted, read that book, write that essay. Sure, a few cheated their way past us, but let’s face it, the ones most likely to cheat were the least likely to get away with it, and we caught a fair bunch of them.

But now there’s AI

But now you no longer have to copy or plagiarize or buy someone else’s work. Your computer will write your paper, take your exam, and its language and answers will be too unique to pin on anyone else.

Of course, we have “AI detectors,” and countless “tells,” and I, myself, have caught students in the act and held them accountable. And yes, I’m moving my students to hard copy, to writing in class, and, if I can keep their cellphones out of their hands (which is not so easy), I can make them do the work.

Until I can’t.

Soon enough, you’ll be able to prompt AI to write in a more individualized,11 undetectable style.12 Soon enough, you won’t need your phone. You’ll be able to use your glasses or a watch or a ring or an implant. . . . What are we going to do, we English professors, to prevent our students from asking AI to write their papers when the AI chip is implanted behind their eyeballs?

We won’t be able to, simple as that. And that’s game over.

We still might be able to convince a few true believers to play along with either the religion of Literature or of the Text, but most will not go along, and we Sunday school teachers will be out of business.

The Jig is Up

Maybe we shouldn’t have been in that business all along. What business did I ever have insisting someone needs to read Shakespeare because I found it meaningful, enlightening? No more business than I had forcing them to learn Hebrew or study the Gospels.

I think many of us teaching English know this but go on teaching anyway because we love it so much. I mean, look, I got paid this semester to teach Interview with a Vampire and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Who would want to give that gig up? And, yes, I do believe my students who didn’t sleep or cheat their way through class gained a meaningful experience. But, I also believe they would have had a meaningful experience learning Torah, and if you paid me to teach them that, I would have taught them that.

I’m a Priest of Culture in a church that’s about to be condemned. I figure the church, the religion, has about ten years or so of life left in it, which brings me to retirement. Do I feel bad for my young colleagues? Of course. Do I feel sorrow at the prospect of my dying religion? Yes, I’ve been mourning it since the 1990s.

An Old Letter to My Old English Prof

I came across this letter today in an old folder. I wrote it as an act of desperation more than 30 years ago during my second year in the University of Chicago’s PhD program. It was addressed to one of my favorite English Professors at Vassar College with whom I studied both Victorian literature and R…

Could I be wrong about this? Yeah, I suppose I could. And I guess I’d be happy if the Sunday school stayed in business. I might even send my son to it, if he wanted. ‘Cause I’m still a true believer. But I just can’t see right now how that’s gonna work.

That and dealing with a case of AI cheating on a final exam.

And, no, it’s not, I hope, because I was hired in 2007. . . .

My course, which I had a blast teaching this semester. I’m only half serious about “patronizing.” It was a course of substance, and I believe in the value of “popular fiction” and horror. But I could have never filled the classroom if it were “Reading Chaucer.”

Or “Language Arts” as they now call it in secondary school—because you wouldn’t want to privilege those damaned English. . . .

Points to anyone who catches the allusion to Weber and Rice. . . .

The very word “canon” is a religious term imported from Catholicism.

See how “no one wants to enroll their kids in Hebrew school” in this post by Liberal Jew Jill.

That being the art of demonstrating that what you are reading doesn’t actually say what people, including the author, think it says, but actually says something quite different, often radically contradictory to the apparent meaning.

There’s a viral post going around now, “English Majors Can’t Read.”

You can probably do it already, but, again, the students most likely to cheat are too lazy to figure out how.

In response today to one of my notes on this idea, one “expert” in the field informed me we are in an AI stall—that its undetectability is maybe never coming, and anyone with discernment can spot AI text. I had ChatGPT respond to his comment. He responded twice to AI-written comments without realizing he was debating with a computer program.

And get this, I ran my AI-written response to Mr. Expert by the same AI that wrote it, and asked was it AI, and ChatGPT had this to say:

This passage doesn’t clearly bear the hallmarks of AI-generated Text—it reads as nuanced, reflective, and personal, with a distinctive voice and rhythm. Its layered argumentation, use of rhetorical framing (“God forbid,” “not anti-tech,” “a chance to feel something from the inside out”), and specific cultural references suggest a human author, particularly one accustomed to intellectual discourse and the careful balancing of ideas.

If this were written by an AI, it would be a particularly well-finetuned one—likely guided by a thoughtful prompt or edited by a skilled human. But as it stands, it feels genuinely authored: emotionally textured, conversational yet precise, and rich in both metaphor and implication.

Would you like a breakdown of specific linguistic cues that typically differentiate AI from human writing?

As an English major (millennial generation), I endorse every word of this article. But as someone who participated in the discipline on the precipice of its decline, here are what I view as the main reasons for it:

1) Lack of reading universally, in every social class. The vast majority of Americans simply don't read, and don't require their kids to. This has been going on for a long time, well before the advent of smartphones.

2) Credentialism replacing real education. College is now for the piece of paper that will lead you to employment and nothing else. For a long time, the English major could do that -- if you went to a top-tier school (as I did), you were more or less guaranteed employment (or admission to professional school) after you graduated. The Great Recession starting in 2008 blew all of that to smithereens.

3) When you get out in the real world, you start seeing that the cheaters, the Spark Notes consumers, and I guess now those who got AI to do their work for them are now in the C-Suite making six figures.

Interesting post. In keeping with your analogy, I think English departments need to take a cue from religion and go more old school and demanding to survive. Think Orthodox Christianity, Catholics who celebrate Latin Mass, and Chabad, not the Episcopalian church, Unitarians, or reform synagogues. You will get fewer, more engaged students seeking an authentic experience, not some watered-down, AI-hybrid.

Most colleges can't and won't do it because they have abandoned the canon and capitulated to post modernism. So they deserve to fail, although I'm sorry for the talented faculty and students who get caught up in the changes.