There are certain prayers I keep tabbed in my siddur (prayer book) so I can find them quickly, important prayers that not only mark key moments in the service. These include “the Shemah,” “the Amidah,” “Ashrei,” and the one I want to talk about today “Aleinu.”1

Aleinu is, by some accounts, what we in academia call “problematic”—a term that itself both names and exemplifies2 a condition in which a phenomenon (or sometimes a person) contains elements or attributes that, in light of current mores, are no longer acceptable, despite other admirable qualities. Thus, for some people, Harry Potter not to mention J.K. Rowling herself is “problematic” because it/she no longer stand up to a certain brand of moral scrutiny.

So what is Aleinu and why is it “problematic?”

Well, it’s a two-paragraph poem/song central to Jewish liturgy that informs us (that is us Jews) of our obligation to praise God, acknowledge him as the only real force in the universe, and thank him for distinguishing us (Jews) from other peoples of the world. It calls upon God to eliminate false idols and predicts that, in the end, everyone will acknowledge the true God’s glory.

Tradition says the prayer was written by Joshua, who inherited the leadership of the Israelites from Moses some 3,400 years ago. We recite it at the end of every service “in order,” according to one commentator “to reinforce our faith in the unity of God’s kingdom before we return from the synagogue” (Rabbi Yoel Sirkes [1561-1640] qtd. in A Call to the Infinite p. 76).

And, as you can see even from my brief summary, the prayer is a little jingoistic. Even some of the great rabbis were uncomfortable with its most infamous line, which states of “the multitudes” that “they bow to vanity and emptiness and pray to a god who does not save.” The ArtScroll Ashkenazi siddur prints this line in parentheses because some congregations still omit these words. The editors explain that in 1400 an apostate Jew “spread the slander that this passage was a slur on Christianity,” and that subsequently the Christian Church pressured Jews to remove the line from European prayer books. According to ArtScroll, “Most congregations have not yet reinstated it” even though “prominent authorities . . . . insist Aleinu be recited in its’ original form.”

Apparently, Reform congregations not only cut those lines but also the one that thanks God that “he has not made us like other nations.”

Now my main problem with Aleinu is not that it’s chauvinistic but that I can never finish the first paragraph before the Chazzan is done intoning the second. But I understand the questions of religious tolerance and pluralism the prayer raises. Is it okay to dismiss and disparage other religions, much less to institutionalize the practice?

The obvious answer would seem to be no. And yet, in truth, almost everyone believes that people outside their spiritual/religious/intellectual community bow to emptiness and vanity.

Jews think Christians are mistaken that Jesus is/was the Messiah. Christians think Jews are sadly missing out on the truth that he is/was and that we needlessly cling to a set of abrogated Laws. Muslims think both Jews and Christians are wrong about the prophets, the Messiah and the Law. All three Abrahamic religions maintain that “pagan” and polytheistic religions foolishly mistake false gods and idols for the true God. And nearly all religions, polytheistic or monotheistic, believe that non-religious people foolishly worship material things—money, pleasure, power—instead of the spiritual. It’s commonplace, by the way, for those who consider themselves “spiritual” to disparage “organized religion.” And many committed atheists, for their part, accuse all brands of religion and spirituality as, essentially, worshipping a “Flying Spaghetti Monster.”

You can say that all this is wrong-headed and “intolerant,” but the fact remains that there are irreconcilable differences between all the major and minor religions, between their subsets, and between the religious and non-religious. So, let’s not pretend we all “respect” each other’s beliefs in the sense that we think ideas that fundamentally contradict our own are equally valid. Some folks might feel that way,3 but few of us really do.

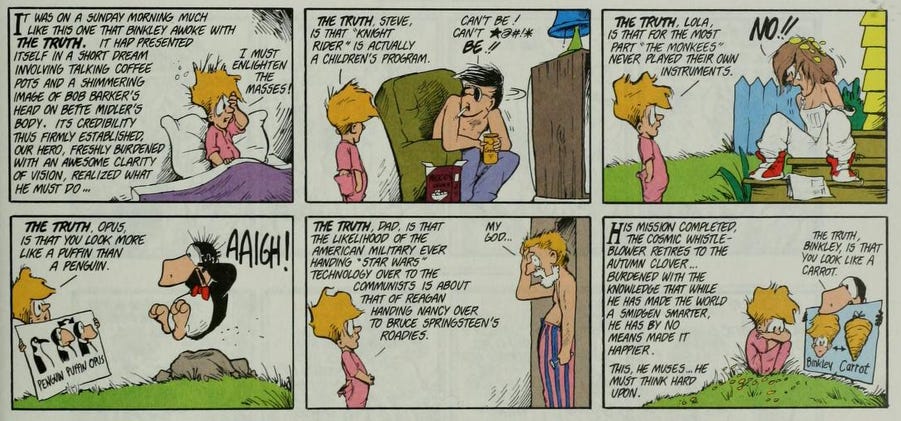

What it really comes down to then is pragmatism. Ought one call out, whether in private or public, other people for holding views with which you disagree if those views aren’t harming anyone? Do you want to be like a certain precocious cartoon character from the 1980s

.4

But the private/public distinction is an important one. It’s one thing to tell Steve Dallas to his face that he’s watching a children’s program; it’s another thing to disparage the show among those who don’t profess to love it.

Jews don’t go around shouting Aleinu on street corners or outside churches or Hindu temples. That’s not our style. It’s a prayer restricted to the synagogue and has no impact outside it.5

Oh, but it does, you may say, because Aleinu reinforces a kind of Jewish bigotry that gets played out in the outside world, the answer to which is, “Yeah, all that Jewish bigotry sure is a problem.” I mean, unless you’re going to get into Israeli politics (which we are not) or Neo-Nazi fantasies (which we are also not) the disdain some Jews feel for the beliefs of non-Jews has little to no impact in the real world. And we ought to remember that Aleinu was incorporated into the prayer service during times when the persecution of Jews was commonplace and when a little counter-disdain was, at least, understandable.

For my part, when I speak those lines, I’m not thinking of any specific religions, maybe not of religion at all, because I believe God made or allowed to be made or whatever all these different religions for a reason. I’ve been Christian, and I know its value, and our disagreements about the identity of the Messiah or about how best to serve God are trivial compared to our disagreements with those who see no value in service to God. When I think of people worshiping vanity, I’m not picturing my friends at church but all the people outside religion chasing after another in search of meaning and purpose.

Still, in truth, if I were writing Aleinu today, I’d probably edit out those lines as unnecessarily “polarizing.” But I didn’t write Aleinu, and it would be chutzpadik of me to pretend I could have, much less that I could have done a better job than Joshua.

You see there’s a fundamental difference between the way Torah observant Jews and contemporary culture look at past generations.

The prevailing notion today is that humanity progresses, albeit with some backsliding, toward greater knowledge, intelligence, and moral understanding and practice. This idea comes in part from Darwin—only the strongest and best ideas survive—but is also a product of our justifiable pride in technological advances.6 People who can build a flying car, nearly eradicate tuberculosis, and stream Fauda probably know a bit more about what is right and wrong than ancient goatherds or medieval “sages” who didn’t even have running water or Netflix.

But observant Jews don’t see it this way. They7 believe the closer you are in history to the giving of the Torah, the greater your spiritual and moral insight. Thus the “Rishonim,” the “first” sages who debated Torah law in the early middle ages are granted greater authority than the “Acharonim,” the “later ones.” The late Rabbi Sachs, for example, was as educated and erudite a rabbi as ever was. He studied philosophy at Oxford in the 1970s. But he couldn’t overrule Maimonides, the twelfth-century rabbi, who, though well-versed in Aristotle knew not a thing about Hegel. And Maimonides, for his part, saw his role as a scholar to elucidate, not to correct, the Tannaim whose ideas as written in the Mishnah predated him by a thousand years.

You might say Orthodox Jews have got things backward in this respect, that we should not bind ourselves to the words and laws of people who lived in such vastly different (and inferior) times. But for me, it comes down to humility. Have I really thought more deeply than Maimonides? Are all those Torah scholars of today and the distant past just rubes who didn’t have the insight, intelligence, and moral fiber that I do?

My feeling is that, at the very least, I ought not engage in historical erasure. Let the lines stand so we can think about them, try to understand where they came from, and what we are to do with them. Moreover, there’s room, so to speak, for interpretation. I, for example, choose to interpret the lines generously, not as some kind of Jewish declaration of superiority but as an expression of gratitude for our tradition and our perception of truth, and a way of acknowledging that, yes, we can’t always reconcile that truth with other people’s, that we don’t just accept whatever alternatives may exist as “equally valid.”

And, if in your place of worship, you make similar assertions, that people who don’t share your belief system are bowing before vanities, if you believe, say, that Jews missed the bus when it comes to the Messiah,8 I’ll try not to take it personally. That’s the kind of pluralism I advocate, not one in which we all have to agree or pretend to agree or keep our disagreements silent and hidden in the most secret corners of our hearts, but one in which we can accept that one of us is probably wrong and that we both think it’s the other guy.

The Shemah is a central Jewish prayer whose climax is the declaration “Shemah (hear) Israel, Adonai our God, is one.” “The Amidah,” i.e. the Standing Prayer, is a prayer of eighteen blessings at the heart of the service. “Ashrei” and “Aleinu” are of lesser stature but, nonetheless, important. They are named for the first words, “Happy” and “Upon us,” respectively.

Interestingly, the word “problematic” itself was recently exposed as a problematic example of elitist jargon by NYT writer David Brooks in this annoyingly pay-walled column.

Or pretend to themselves that they do.

Who is wrong about the Monkees, btw,. . . sort of.

Though in the spirit of openness, I should mention that tradition says it was Joshua’s repetition of this prayer seven times that brought down the walls of Jericho.

Some people, to be fair, would also point to increased freedom and tolerance as an example of our moral superiority over the past. But this begs the question of whether freedom and tolerance have any downsides, morally speaking, and how can we measure these against previous ages.

The pronoun used here, to be honest, is evidence of some ambivalence on my part about this notion. I might need to return to this idea in a future column or article.

A fond memory of mine from my first trip to Israel is of a guide telling a group of tourists how we’ll ultimately know who is right about Jesus. If, when the Messiah comes, he says, “Nice to see you,” it was the Jews. If he says, “Nice to see you again,” it was the Christians.