It’s a common question, actually.

George Orwell asked it and came up with four reasons:

Egoism— the “desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood.”1

Pleasure in the production of beauty.

The historical impulse “to see things as they are and store them up for the use of posterity.”

The political desire to “push the world in a certain direction.”

Joan Didion asked it as well. She notes that every word of the question contains, phonetically, an “I” as in “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see, and what it means. What I want and what I fear.”2

But it’s one thing to be George Orwell, author of two of the most influential novels of the twentieth century, or to be Joan Didion, a lauded journalist, screenwriter, and essayist musing in The New York Times, and quite another to be, well, me—a guy who, at age 61, despite being a full professor and teacher of Creative Writing, still struggles to place a short story in journals that, in truth, hardly anyone reads.

And yet I keep writing.

I finished a story yesterday that may take me a year or more to place, if it gets placed at all.3 And I keep writing this Substack, now going on its second year, with what can be considered at best a modest subscriber base. And sometimes I ask myself why.

Of course, one obvious reason is that I have to, to keep my job. I may be a tenured professor, but if I don’t keep publishing, one of these days my boss is going to check the dreaded “does-not-meet-expectations” box on my annual review, and though the administration would have to jump through some hoops, I could lose my cushy job.

But, of course, that raises the question of why I took the job in the first place, the answer to which is not just that I wanted my summers off but also that I wanted a job that would make me write4 because I don’t always feel like it. My life, my writing career, has been one long vacillation between pressured productivity and studied avoidance.

Over the last couple of years, that has been less the case, in large part because of Substack, where the pursuit of likes, comments, restacks, and a few hundred dollars a year has resulted in one of the more productive writing periods of my life.

If you consider writing a newsletter productive—which my bosses don’t.

So, the question remains, why do I write? Because, at least on Substack, the writing “doesn’t count” toward keeping my phony baloney job.

For that, I’ve got to publish in something peer-reviewed.

Funny story. At a recent department meeting, we were asked to share “good news,” which basically means publications. I am not exaggerating when I say that persons to the right of me, behind me, behind and to the right of me, and in front of me all reported news of books coming out.

I have one book that came out in 20125, and no prospects of one anytime soon.

My good news? This summer, I published an article in Quillette predicting the end of English Departments.

I did not raise my hand to share my good news.

I sometimes ask my students, “Why do you write?”

The answer I least like is “to express myself.”

That usually goes along with “I just write for myself,” which, in turn, usually means the student doesn’t want to revise, adapt, or improve their work because, why should they? It’s just for themselves. They know what they mean. They get their own inside jokes. They know everything that’s implied but not stated.

I don’t really believe it when people taking a Creative Writing class say they just write for themselves. Most writers, nearly all, want people to read their work, lots of people.

The best answer I’ve gotten is, “I write because I want to make other people feel the way I felt when I first read writing that I love.”

That is a terrific reason to write.

The reason I give?

Because I didn’t get enough attention from my parents when I was a child.

And yet, this idea of “writing for yourself” is not entirely wrong.

Over the years, I’ve increasingly come to the point where I’m like, I’m going to write what I like and how I like.

So, whereas I used to feel pressured to write “literary fiction,” I now write horror—though in truth it is “literary horror.” But I don’t write literary style horror because “I’m supposed to” but because that’s what comes naturally for me.

And nowadays, I don’t hesitate to drop in allusions and gags that only a Gen Jones/Last Chance Boomer would get. Because it’s fun, and I know somebody’s going to get it.

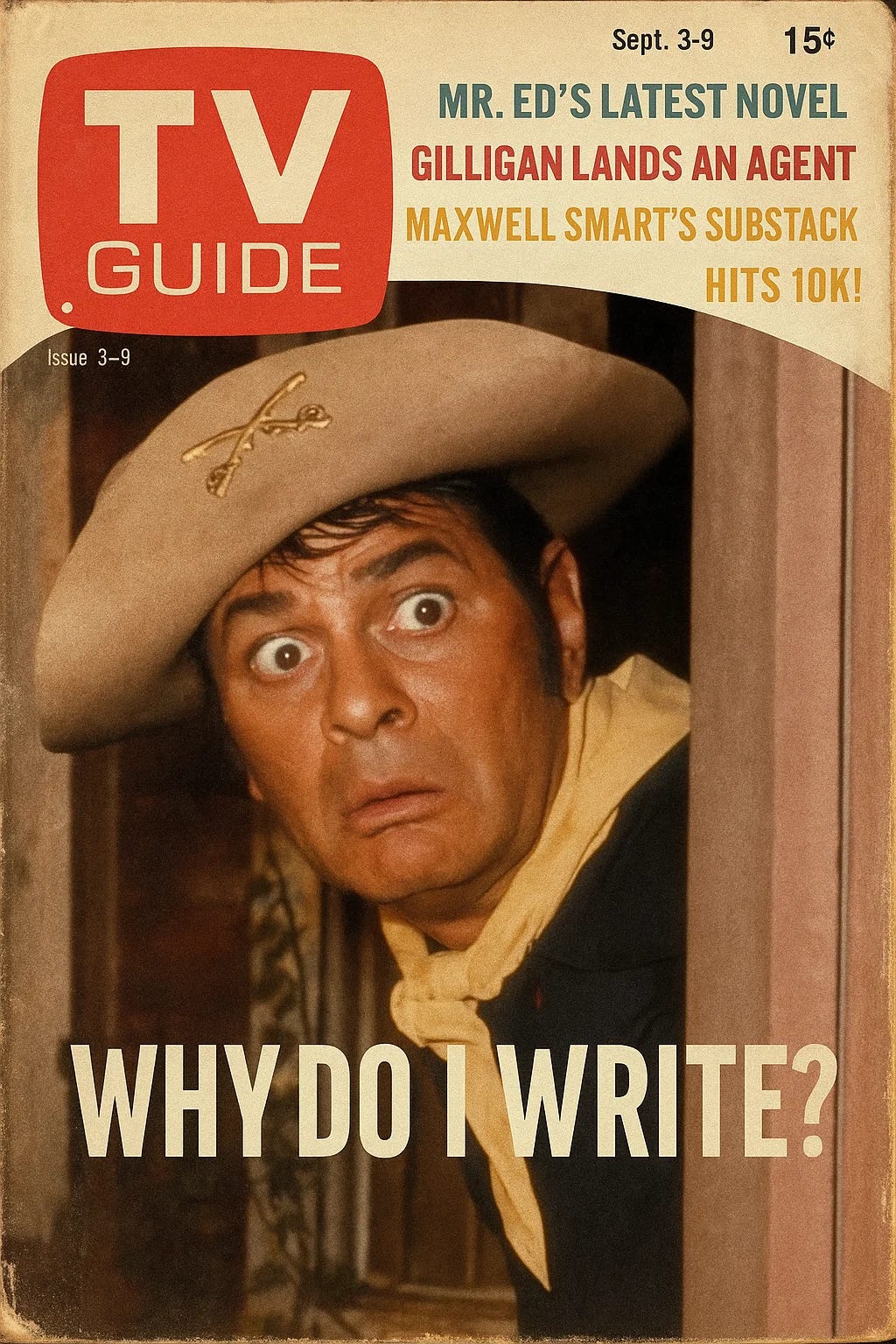

I’ve resigned myself to an audience of what the poet John Milton, author of Paradise Lost, called “fit but few,” though by that he meant really smart people who’ve read the Bible backwards and forwards a bunch of times, whereas what I mean by it is people who used to watch F-Troop.

Where is all this going?

I don’t know.

It’s the last week of my summer.

Classes start on Monday, and I’ll have to model the old “those-who-can’t-do, teach” approach to the life of a successful writer.

And I’ve got stuff on my mind and a story I really like, but that I’m skeptical will find a place because, among other things, it’s so steeped in late 70s suburban teenaged miscreant guyness.

Whatever. Maybe I do only write for myself.

A man after my own heart.

Italics mine.

It does not, however, answer the question of why they hired and promoted me, which is something I ask myself rather frequently nowadays. . . .

Out of print, but available for free on “Kindle Unlimited” or to buy on Kindle for $2.99. Or you could buy a hard copy directly from the author by messaging me, or become a Founding Member of this Substack and get a signed one as a thank-you gift.

I write because I feel I have what to teach people and I like the dopamine rush of their reactions

"I write because I want to make other people feel the way I felt when I first read writing that I love." I hope you gave that student an "A."