I posted this last week on my alternative Substack, “Not-So-Perplexed,” but a trusted reader pointed out that it’s more in line with this Substack, so I’m reposting it here (with one new footnote). Apologies to those of you who’ve already read it, and for those who haven’t, I hope you’ll enjoy it.

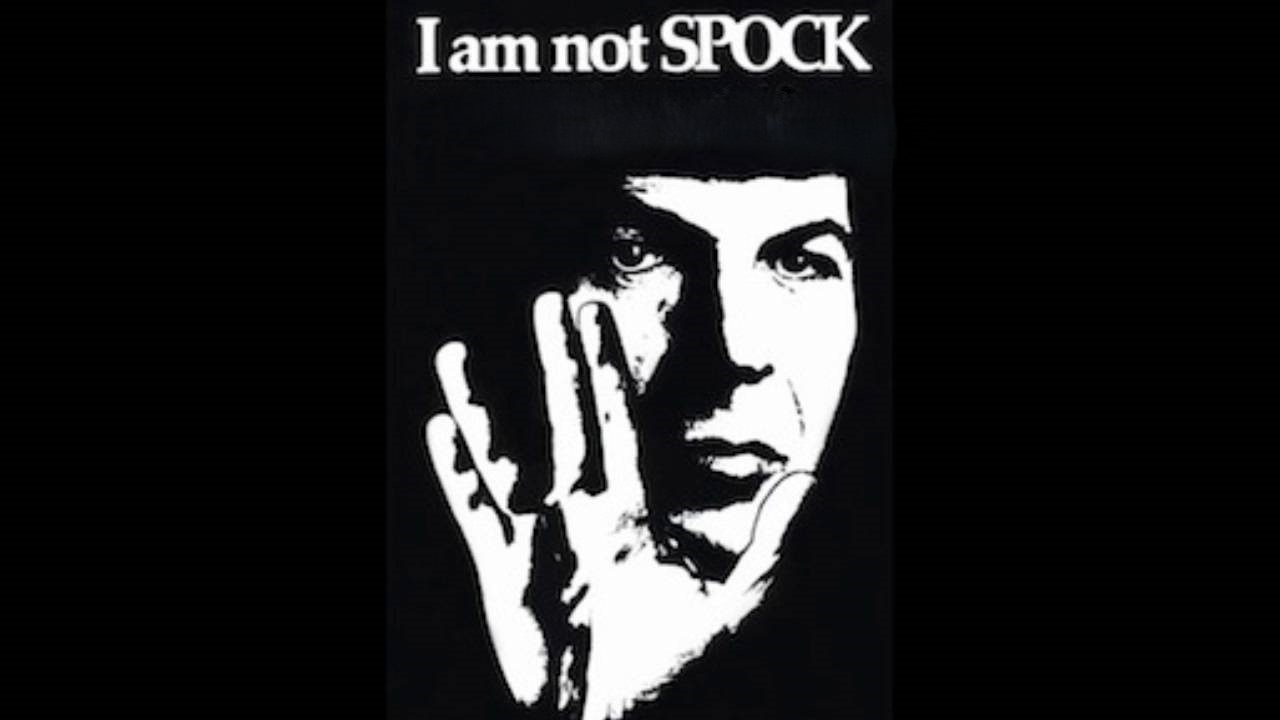

In 1975, six years after the cancellation of Star Trek and a year after the end of the stellar animated version of the show, Leanord Nimoy published his autobiography entitled, I am not Spock.

Many people, myself included,1 took this title as a slam against the beloved character Nimoy played on TV and were hurt by it. It felt as if Nimoy was dissing Spock, disowning him, which seemed both ungrateful and unkind since that character rocketed Nimoy to fame and because Star Trek fans were so moved by Spock.2

But, of course, none of us who reacted that way actually read the book.3 Later, in interviews, Nimoy explained that he was not putting down the character of Spock but merely trying to emphasize that he, that is Nimoy himself, was more than the fictional character he played for some four seasons, that he was an actor with an already respectable history in film and TV, a poet, and a human being with a life separate from the Sci-fi icon he became.4

It is in this spirit that I declare, “I am not a Zionist,” though I fully expect that, as with Nimoy’s book, I’ll get some reaction from folks who don’t read the article—or don’t read it carefully.5

Here’s what I don’t mean when I say I am not a Zionist. I don’t mean that I don’t support the State of Israel in its current war against Hamas or that I am in any way against Israel.

On the contrary, more than believing in “Israel’s right to exist” and its “right to defend itself,” I firmly maintain that the very question of Israel’s right to exist is nonsensical, that its existence is every bit as legitimate as any other country in the world and more legitimate than many, and that concerning defense, it’s not a “right” it’s a duty. Israel has a moral obligation to defend its people, its borders, and its sovereignty.

More specifically, I believe Israel is correct to prosecute this war on Hamas and to eliminate Hamas as a functional military and administrative organization. And I’m agnostic on the two-state solution, leaning toward seeing it as unrealistic for the foreseeable future.

But I don’t call myself a Zionist.

Why? Because the moment you attach an “ist” to yourself, you have limited your identity and committed yourself to abstract ideas in ways that I can’t endorse, that, in fact, I actively oppose.

Let’s face it. We’re all living with the hangover of the Twentieth Century. For those with little sense of history, it’s all about World War II. For the rest of us, it’s also about the broader swath of political violence that dominated that long century.

For as long as I can remember, the blame for WWII has been placed on nationalism, which is one of the reasons why elites tend to be anti-Israel because Israel seems like a throwback to the idea “that got us here in the first place.” But nationalism is just half the picture, maybe not even half. The real culprits of the Twentieth Century were the various “isms”: Marxism, Leninism, Maoism, Fascism, and Communism (and the real troublemakers of the Twenty-First Century have been poststructuralism, postmodernism, feminism, and postcolonialism—not necessarily in that order).

It was the struggle, often violent, often in the streets, between Marxists and fascists that facilitated the rise of Hitler and Mussolini. It was Communism/Lenninsm that enslaved the Soviet Block for some 70-plus years and resulted in millions of deaths through imprisonment, execution, and mass starvation, likewise for Communism/Maoism in China. I guess for good measure, we could throw in Imperialism as well, which would explain the Japanese atrocities against China and Korea.

The moment you attach “ism” to an idea or identity, you divorce it from experience, and the moment you attach it to yourself, you separate yourself from whole swaths of humanity. “Isms” grow out of theory. They are the product of an irrational attachment to the products of human reason, so that what ought to be treated as speculation and even idealization becomes reified,6 made literal and then sacrosanct.

Here’s an example that will doubtlessly irritate friends, family, colleagues, and readers: feminism. Before that word was much in play, people spoke about “women’s rights,” “the woman question,” “suffrage,” and so forth. But the moment “feminism” came into play, we were no longer talking about equality before the law but of an active preference for and advocacy of women’s interests over that of men.

You can blah blah blah all you want about “feminism just means believing that women have equal rights with men,” but that’s not what it has meant in practice to a lot of people who took on that term. From Gloria Steinem to Andrea Dworkin to Judith Butler, feminism has meant seeing things through a lens that only reveals power structures oppressing women. That is why, for example, when a basically liberal YouTuber like ShoeOnHead expresses even a modicum of sympathy for young men, she gets pilloried by feminists. That’s why scholars of the 19th century like Gilbert and Gubar7 could rail about the oppression of bourgeois Victorian wives but scarcely had a word to say about the use of men as cannon fodder, the Shanghaiing of sailors, or the plight of young boys shipped off to boarding schools. The term not only implies but installs a myopic view of the world in which all that matters is how women are affected.8

The answer is not a counter ism, an espousal, say, of “masculinism” such as we see in the so-called Red Pill influencers. The answer is a broader application of existing ideas of human liberty and justice. It’s been a while, for example, since I read John Stuart Mill’s The Subjection of Women, but I don’t recall him using the word “feminism,” much less attaching it to himself.9 And I’m pretty sure none of the men who voted in favor of women’s suffrage used such a label.10 You don’t need to be a feminist to support women, women’s rights, or equality between the sexes.

I used to say I was a “humanist,” but I’ve come even to reject that form of ism because I realized it denotes an approach to life that excludes the divine and so has become a synonym for “atheist.” “Humanist” puts too much faith in the power of people to solve problems; it’s the source of what I call the Disney philosophy: all our dreams can come true, an appealing, but ultimately false and dangerous, idea.11

So, I don’t say I’m a humanist; I say I believe in Constitutional rights or God-given rights, equality of opportunity if not outcome, freedom of speech, etc.

The thing is, nearly every “ist” is a variety of fascist because “ist” always insists, often with the threat of violence, that you buy their program wholesale, keep your doubts to yourself, and wear the red ribbon.

And what about Zionism? Doesn’t it just mean you support Israel, that you believe it’s the homeland of the Jews? Isn’t Zionism a central tenant of Judaism? Well, maybe in common parlance, yes, but, in fact, no.

When I think of Zionism, I think of Jabotinsky. I think of the lyrics from his song, “The East Bank of Jordan.”

Two Banks has the Jordan – This is ours and, that is as well.

In other words, Jabotinsky’s Israel includes what we now think of as the nation of Jordan. This is what a Zionist map of Israel looks like in his dream.

I’m not saying this is what Zionists want today, but what I am saying is that the term “Zionism,” by virtue of being an ism, suggests to me a kind of dogma, a deliberate myopia that sees only the interests of the people whom the term encapsulates and that the term “Zionist” reduces me as a person. I’m not Tom, the writer, husband, father, friend, Jew, ukululeist. I’m Tom, the Zionist.

Look, I don’t just support Israel because I’m a Jew, and I don’t expect other people to do so because they love Jews. I expect people to support Israel because that’s consistent with Western ideals of freedom and because it’s consistent with the self-interest of Western nations, including my own, the United States. You don’t have to love Israel or even much like Jews to recognize it’s in the interest of all freedom-loving folk that the likes of Hamas be soundly defeated. And, by contrast, the ideologically-driven—and historically uniformed—children protesting on college campuses need to be taught that it is their own freedom, not the Jewish state, that they are trying to overturn.

I get that it’s a lot easier to say that “anti-Zionism is anti-Semitism” than it is to say “wishing away the state of Israel” or “indifference to Jewish lives” is anti-Semitism, but we are people, not dishwasher detergent. We don’t need to, and ought not to, organize our lives around slogans, brand names, and clever taglines.12

One more thing: I get that a lot of what I’ve been saying about “isms” could and has been said of religion, and seeing as how I identify publicly as a Jew, this could seem inconsistent, if not hypocritical. After all, don’t I support Judaism?

Yes, I do.

Here’s the difference as I see it. All the other isms I’ve been discussing are theoretic constructs borne out of secular philosophy that privileges human reason above all else, which basically says we’ve figured it out. We know the problem. We know the solution. And we’re going to convince you, by rhetoric if possible, by politics if not, by political violence if that doesn’t work, that we’re correct.

A religion such as Judaism, which puts its faith in God and scripture, has to practice a certain amount of humility13—or at least, I would argue, that’s largely what it does in the modern world. Forget about wiping out idolotors in ancient Israel. If you walk into any Orthodox synagogue today, you’ll find that 99% of the sermons, lessons, and discussions are devoted to improving yourself, being a better person, and improving one’s relationship with God. Nary a word is said about changing other people, much less the world, except through personal transformation.

That’s an ism I can get on board with because it basically reiterates the idea that I need to make my own bed before finding fault with the world. It’s the same idea that Jesus had when he advised taking the beam out of your own eye before complaining of the splinter in someone else’s.

Even so, I don’t say I’m a Judeaist.

I’m simply a Jew, sometimes perplexed. Sometimes, not so much.

I was 11 at the time.

I have always identified with Spock, a man who has difficulty feeling and expressing emotions. His character features prominently in the title story of my short story collection, Omicron Ceti III.

I still haven’t, though I’m putting it in my Amazon cart right this minute.

And now that I think about it, maybe what really offended fans like me was that the book took away our fantasy that Leanard Nimoy really was Spock. It’s frustrating when you love a TV character so much and are forced to confront the reality that the actor isn’t really that person. Against all reason, we want such actors to turn into their characters, which has only happened maybe once in history: in the case of the Monkees. “After completing our first tour as a four-piece band in late 1966, Nez [Mike Nesmith] perceptively remarked that ‘Pinocchio had become a real little boy,'” [Micky] Dolenz [told Rolling Stone]. In another interview, Dolenz aptly remarks, “It was like Leanard Nimoy really becoming a Vulcan.”

That having been said, he “did teshuva” some years later when he penned a second autobiography, this time titled I am Spock. I haven’t read that one either.

Fancy word I learned in grad school and toss around when I want to flex my PhD bonafides, but really, it’s more like a war wound. It means to “thingify,” i.e., to treat as real or solid what is more like a metaphor.

I know, I’m dating myself.

This is one of the reasons why, I would argue, that Dworkin and MacKinnon’s war on porn failed because all they focused on was the plight of women as if a. there weren’t male porn actors and as if b. the disproportionate consumption of porn by men didn’t have a disproportionate deleterious effect on the male psyche.

I checked. The word doesn’t appear in the book.

Though admittedly, there were “suffragists” and maybe this is the exception to the rule I’m laying out here. Suffragism disappeared after it achieved its goals. But broader “ist” movements never achieve their goals because they are not specific enough; they are interest-based rather than concrete goals and so whenever they achieve a win, it is not enough. They “move the goalposts,” come up with new goals, and frequently deny that any win has been achieved at all because to do so would be to take the steam out of the movement. Douglas Murray addresses this idea nicely in the introduction to his book “The Madness of Crowds.”

As referenced in my YouTube video “What is Englightenment.”

Says “the Perplexed Jew.”

And maybe this is the difference between “Islam” and “Islamist.”

This is excellent. I’ve talked about this stuff a lot, but you’re doing it better. There are not nearly enough people pointing out that passionate self-identification with isms and orthodoxies is dangerous for all of us, and often counter-productive to the professed aims. I’m putting this in my archive for future reference.

(Respectfully, and quietly, i mention the misspelling of Steinem and the Freudian typo “Andrew” Dworkin.)

Excellent piece. I was trying to figure out what historical uniforms the college protestors were wearing, and then I realized that "uniformed" should be "uninformed." English is a very interesting language.